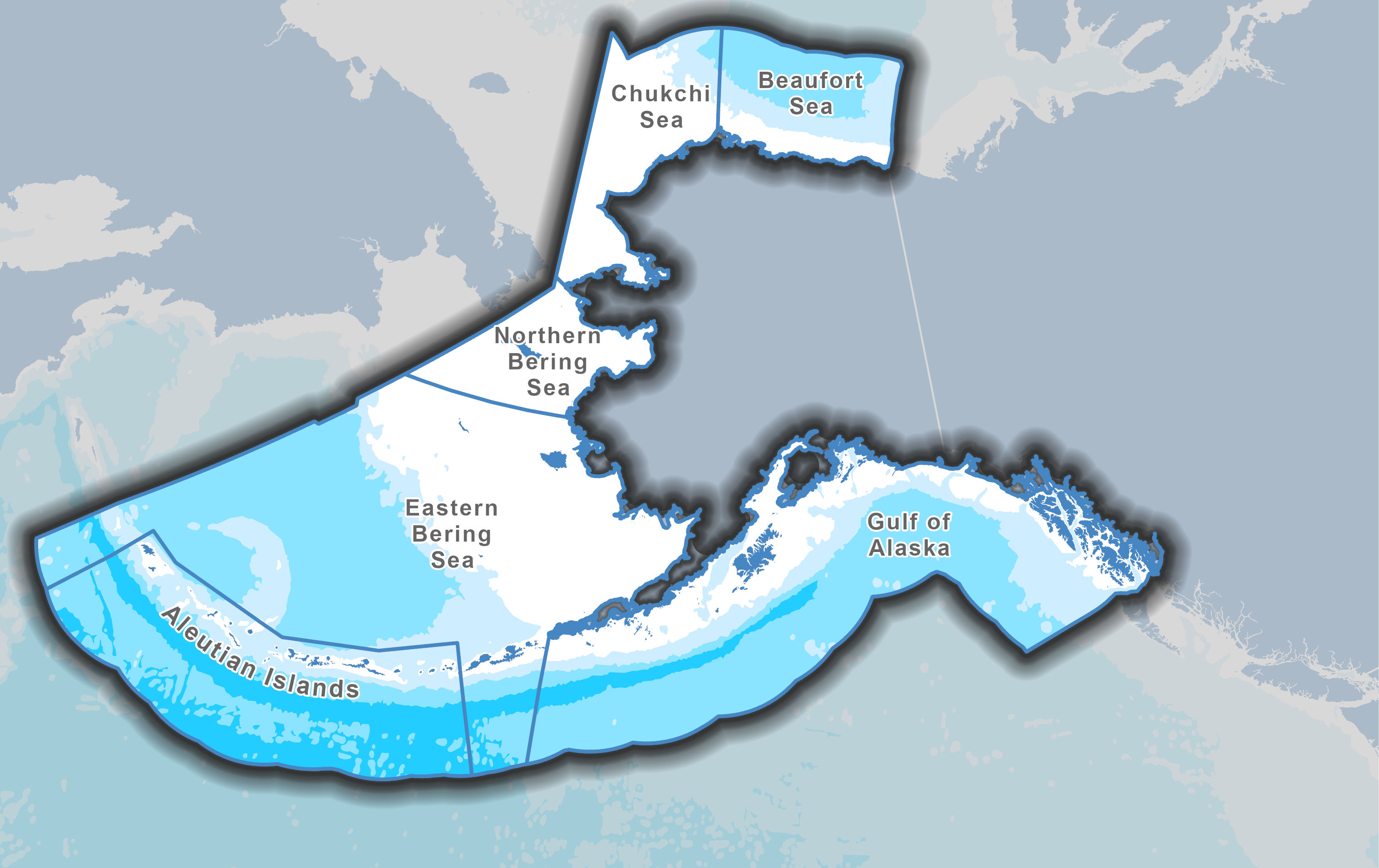

At 44,000 miles long, Alaska’s shoreline is more than double the length of the East and West coasts of the United States combined. It provides diverse habitats for marine life, and supports important ecosystem services for Alaska’s communities and economy. The Alaska region is made up of 6 distinct ecosystems: the Gulf of Alaska (GOA), Aleutian Islands (AI), Eastern Bering Sea (EBS), the Northern Bering Sea, and Chukchi Sea and Beaufort Sea (referred to here as the Alaskan Arctic). These ecosystems support extensive high-value commercial fisheries, indigenous community’s subsistence uses, oil and gas development, and other economic and cultural uses. Each of these high latitude ecosystems is distinct in structure, function and human activity. Indicators are presented for these marine ecosystems as a regional composition, unless otherwise noted.

Over half of the US commercial seafood harvest comes from Alaska, and the Aleutian Islands are a major transit for the Great Circle Route - linking commerce from the U.S. west coast to southern Asia. No other marine system in the U.S. has such extreme weather and climate, vast geographic distances (larger than all other U.S. marine systems combined), and such an extensive coastline.

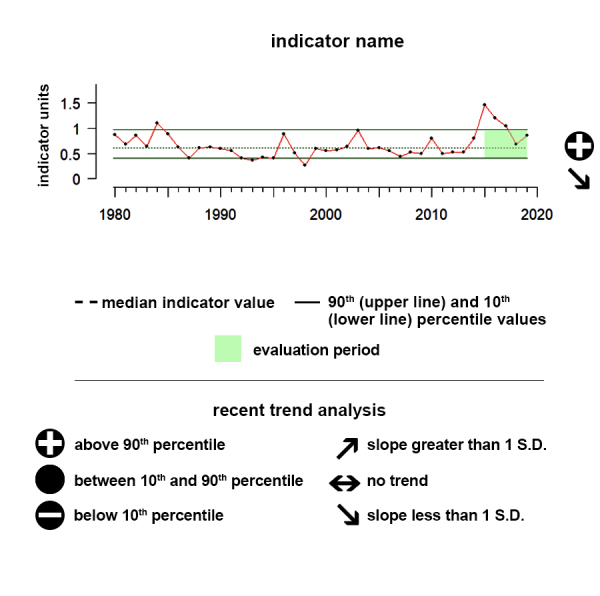

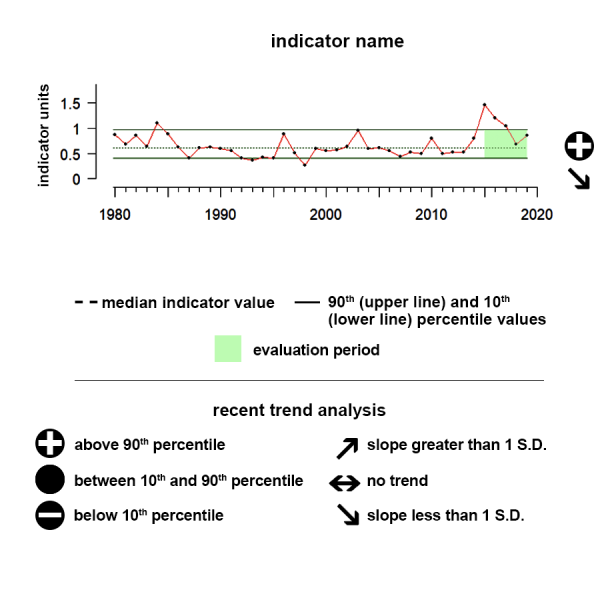

Understanding the Time series plots

Time series plots show the changes in each indicator as a function of time, over the period 1980-present. Each plot also shows horizontal lines that indicate the median (middle) value of that indicator, as well as the 10th and 90th percentiles, each calculated for the entire period of measurement. Time series plots were only developed for datasets with at least 10 years of data. Two symbols located to the right of each plot describe how recent values of an indicator compare against the overall series. A black circle indicates whether the indicator values over the last five years are on average above the series 90th percentile (plus sign), below the 10th percentile (minus sign), or between those two values (solid circle). Beneath that an arrow reflects the trend of the indicator over the last five years; an increase or decrease greater than one standard deviation is reflected in upward or downward arrows respectively, while a change of less than one standard deviation is recorded by a left-right arrow.

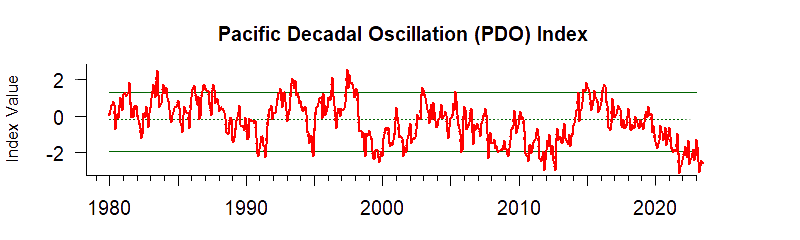

Pacific Decadal Oscillation (PDO)

During the last five years, the PDO indicator has trended downward, shifting from positive phase to negative phase in 2019.

Values correspond to Index scores

Description of time series:

Positive PDO values typically mean cool surface water conditions in the interior of the North Pacific Ocean and warm surface waters along the North American Pacific Coast while negative PDO conditions typically mean warm surface water conditions in the interior to the North Pacific Ocean and cool surface waters along the North American Pacific Coast. During the last five years, the PDO indicator has trended downward, shifting from positive phase to negative phase in 2019.

Description of Pacific Decadal Oscillation (PDO):

The Pacific Decadal Oscillation (PDO) is a long-term pattern of Pacific climate variability that comprises multiple physical forcing mechanisms. The extreme phases of this climatic condition are classified as warm or cool, based on deviations from average ocean temperature in the northeast and central North Pacific Ocean. When the PDO has a positive value, sea surface temperatures are below average (cool) in the interior North Pacific and warm along the Pacific Coast. When the PDO has a negative value, the climate patterns are reversed, with above average sea surface temperatures in the interior and sea surface temperatures below average along the North American coast. On shorter timescales a positive (negative) PDO is often related to El Niño (La Niña). The PDO waxes and wanes on longer timescales as well; warm and cold phases may persist for decades. Major changes in northeast Pacific marine ecosystems have been correlated with phase changes in the PDO. Warm phases have seen enhanced coastal ocean biological productivity in Alaska and inhibited productivity off the west coast of the United States, while cold PDO phases have seen the opposite, north-south pattern of marine ecosystem productivity. We present data from the Pacific Islands, Alaska, and California Current regions

Data Background:

Climate indicator data was accessed from the NOAA NCEI (https://www.NCEI.noaa.gov/teleconnections/pdo/data.csv). The data plotted are unitless and based on Sea Surface Temperature anomalies averaged across a given region.

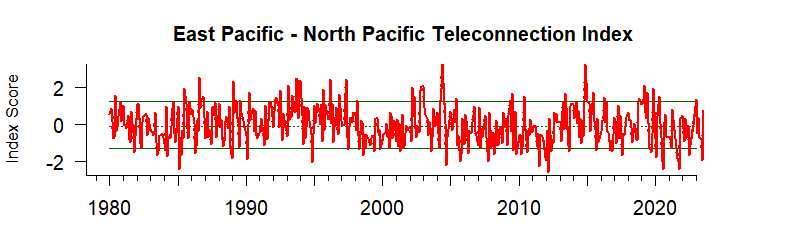

East Pacific - North Pacific Teleconnection Pattern Index (EP-NP)

During the last five years, the EP-NP indicator has shifted from mostly positive to mostly negative.

Values correspond to Index scores

Description of time series:

Positive EP-NP values mean above-average surface temperatures over the eastern North Pacific, and below-average temperatures over the central North Pacific and eastern North America and the opposite for negative EP-NP values. During the last five years, the EP-NP indicator has shifted from mostly positive to mostly negative.

Description of East Pacific/ North Pacific Teleconnection Pattern Index:

The East Pacific/ North Pacific Teleconnection Pattern Index is a measure of climate variability. Positive EP-NP values mean above-average surface temperatures over the eastern North Pacific, and below-average temperatures over the central North Pacific and eastern North America and the opposite for negative EP-NP values.

This climate condition impacts people and ecosystems across the globe and each of the indicators presented here. Interactions between the ocean and atmosphere alter weather around the world and can result in severe storms or mild weather, drought, or flooding. Beyond “just” influencing the weather and ocean conditions, these changes can produce secondary results that influence food supplies and prices, forest fires and flooding, and create additional economic and political consequences. The positive phase of the EP-NP pattern is associated with above-average surface temperatures over the eastern North Pacific, and below-average temperatures over the central North Pacific and eastern North America. The main precipitation anomalies associated with this pattern reflect above-average precipitation in the area north of Hawaii and below-average precipitation over southwestern Canada

Data Background:

Climate indicator data was accessed from NOAA NCEP (https://ftp.cpc.ncep.noaa.gov/wd52dg/data/indices/epnp_index.tim). The data plotted are unitless anomalies.

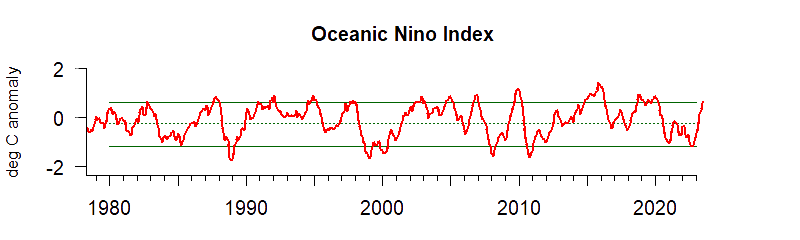

El Niño-Southern Oscillation (Oceanic Niño Index)

The ONI shifted from La Nina conditions to neutral conditions in early 2023, and with continued sea-surface warming now indicate that an El Nino has begun.

Values correspond to Index scores

Description of time series:

The Oceanic Niño Index (ONI) is NOAA’s primary index for monitoring the El Niño-Southern Oscillation climate pattern. It is based on Sea Surface Temperature values in a particular part of the central equatorial Pacific, which scientists refer to as the Niño 3.4 region. Positive values of this indicator, greater than +0.5, indicate warm El Niño conditions, while negative values, less than -0.5, indicate cold La Niña conditions. Values between +0.5 and -0.5 are considered ENSO neutral. The ONI shifted from La Nina conditions to neutral conditions in early 2023, and with continued sea-surface warming now indicate that an El Nino has begun.

Description of El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO):

El Niño and La Niña are opposite phases of the El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO), a cyclical condition occurring across the Equatorial Pacific Ocean with worldwide effects on weather and climate. During an El Niño, surface waters in the central and eastern equatorial Pacific become warmer than average and the trade winds - blowing from east to west - greatly weaken. During a La Niña, surface waters in the central and eastern equatorial Pacific become much cooler, and the trade winds become much stronger. El Niños and La Niñas generally last about 6 months but can extend up to 2 years. The time between events is irregular, but generally varies between 2-7 years. To monitor ENSO conditions, NOAA operates a network of buoys, which measure temperature, currents, and winds in the equatorial Pacific.

This climate pattern impacts people and ecosystems around the world by affecting large scale areas of tropical convection, and by extension, the jet streams. Interactions between the ocean and atmosphere alter weather globally and can result in severe storms or mild weather, drought or flooding. Beyond “just” influencing the weather and ocean conditions, these changes can produce secondary results that influence food supplies and prices, forest fires and flooding, and create additional economic and political consequences. For example, along the west coast of the U.S., warm El Niño events are known to inhibit the delivery of nutrients from subsurface waters, suppressing local fisheries. El Niño events are typically associated with fewer hurricanes in the Atlantic while La Niña events typically result in greater numbers of Atlantic hurricanes.

Data Background:

ENSO ONI data was accessed from NOAA’s Climate Prediction Center (https://origin.cpc.ncep.noaa.gov/products/analysis_monitoring/ensostuff/ONI_v5.php). The data are plotted in degrees Celsius and represent Sea Surface Temperature anomalies averaged across the so-called Niño 3.4 region in the east-central tropical Pacific between 120°-170°W and 5°S-5°N .

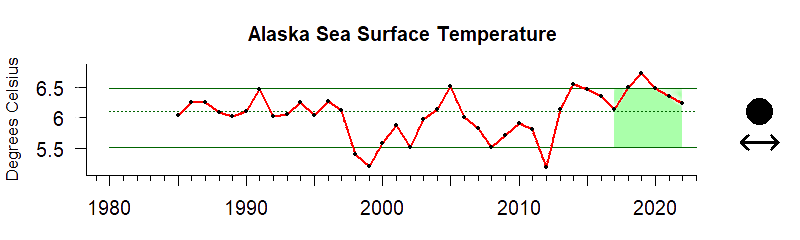

Sea Surface Temperature

During the last five years there has been no notable trend and values have remained within the 10th and 90th percentiles of all observed data in the time series.

The time series shows the integrated sea surface temperature for the Alaska region. During the last five years there has been no notable trend and values have remained within the 10th and 90th percentiles of all observed data in the time series.

Indicator and source information:

The SST product used for this analysis is the NOAA Coral Reef Watch CoralTemp v3.1 SST composited monthly (https://coralreefwatch.noaa.gov/product/5km/index_5km_sst.php) accessed from CoastWatch (https://oceanwatch.pifsc.noaa.gov/erddap/griddap/CRW_sst_v3_1_monthly.g…).

Great Lakes SST data were accessed from (https://coastwatch.glerl.noaa.gov/glsea/glsea.html).

The data are plotted in degrees Celsius.

Data background and limitations:

The NOAA Coral Reef Watch (CRW) daily global 5km Sea Surface Temperature (SST) product, also known as CoralTemp, shows the nighttime ocean temperature measured at the surface. The CoralTemp SST data product was developed from two, related reanalysis (reprocessed) SST products and a near real-time SST product. Spanning January 1, 1985 to the present, the CoralTemp SST is one of the best and most internally consistent daily global 5km SST products available. Monthly composites were used for this analysis.

Documentation: https://coralreefwatch.noaa.gov/product/5km/index_5km_sst.php

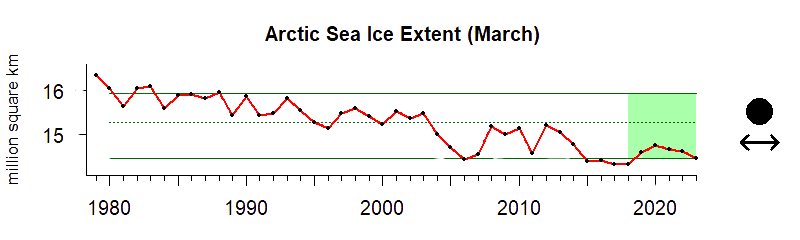

Sea Ice Extent

During the last five years, there has been no notable trend and values are within the 10th and 90th percentiles, albeit near the lower end of the time series.

Sea ice is an important element of the Arctic system. We present the annual Arctic sea ice extent in units of millions of square kilometers.

Data Interpretation:

This time series shows the sea ice extent for the Alaska-Arctic region from 1979 to 2023. During the last five years, there has been no notable trend and values are within the 10th and 90th percentiles, albeit near the lower end of the time series.

Indicator and source information:

Sea ice is ice that forms, expands, and melts in the ocean. Sea ice has an important effect on Earth’s heat balance by reflecting solar energy back to space; it also plays a role in determining ocean salinity and currents, and it provides important habitat for many marine organisms.

The time series shows the Sea Ice extent in September of each year to give a sense of the summertime (i.e., minimum annual) extent through the years of sea ice across the entire Northern Hemisphere, which includes the Arctic Ocean and the Hudson Bay.

Data background and limitations:

Sea ice figures and data was accessed from NOAA NCEI for the northern hemisphere, https://www.ncei.noaa.gov/access/monitoring/snow-and-ice-extent/ The data are plotted in units of millions of square km.

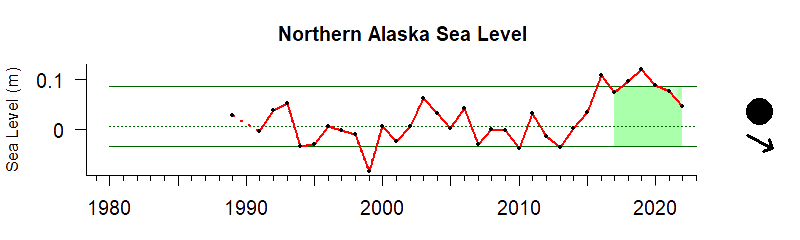

Sea Level - Chukchi and Beaufort Seas

During the last five years, there has been a decreasing trend and values are between the 10th and 90th percentiles.

Sea level varies due to the force of gravity, the Earth’s rotation and irregular features on the ocean floor. Other forces affecting sea levels include temperature, wind, ocean currents, tides, and other similar processes.

Description of time series:

The time series shows the relative sea level for this region. During the last five years, there has been a decreasing trend and values are between the 10th and 90th percentiles.

Indicator and source information:

NOAA monitors sea levels using tide stations and satellite laser altimeters. Tide stations around the globe tell us what is happening at local levels, while satellite measurements provide us with the average height of the entire ocean. Taken together, data from these sources are fed into models that tell us how our ocean sea levels are changing over time. For this site, data from tide stations around the US were combined to create regionally averaged records of sea-level change since 1980. We present data for all regions.

This indicator includes tide gauges from Nome and Prudhoe Bay, AK.

Data background and limitations:

Sea level data presented here are measurements of relative sea level, water height as compared to nearby land level, from NOAA tide gauges that have >20 years of hourly data served through NOAA’s Center for Operational Oceanographic Products and Services (CO-OPS) Tides and Currents website. These local measurements are regionally averaged by taking the median value of all the qualifying stations within a region. The measurements are in meters and are relative to the year 2000.

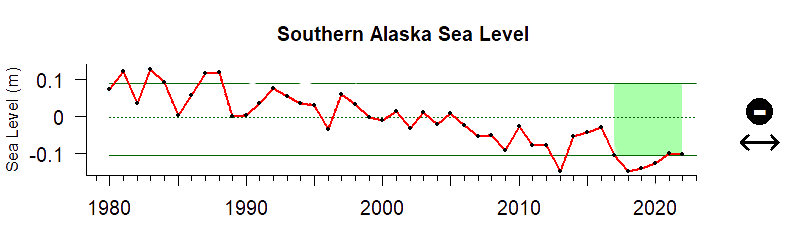

Sea Level - Gulf of Alaska and Eastern Bering Sea

During the last five years, there has been no trend yet values are below the 10th percentile.

Sea level varies due to the force of gravity, the Earth’s rotation and irregular features on the ocean floor. Other forces affecting sea levels include temperature, wind, ocean currents, tides, and other similar processes.

Description of time series:

The time series shows the relative sea level for this region. During the last five years, there has been no trend yet values are below the 10th percentile.

Indicator and source information:

NOAA monitors sea levels using tide stations and satellite laser altimeters. Tide stations around the globe tell us what is happening at local levels, while satellite measurements provide us with the average height of the entire ocean. Taken together, data from these sources are fed into models that tell us how our ocean sea levels are changing over time. For this site, data from tide stations around the US were combined to create regionally averaged records of sea-level change since 1980. We present data for all regions.

This indicator includes tide gauges from Ketchikan, Sitka, Juneau, Skagway, Yakutat, Cordova, Valdez, Seward, Seldovia, Nikiski, Anchorage, Kodiak Island, Sand Point, Adak Island, Unalaska, and Port Moller, AK.

Data background and limitations:

Sea level data presented here are measurements of relative sea level, water height as compared to nearby land level, from NOAA tide gauges that have >20 years of hourly data served through NOAA’s Center for Operational Oceanographic Products and Services (CO-OPS) Tides and Currents website. These local measurements are regionally averaged by taking the median value of all the qualifying stations within a region. The measurements are in meters and are relative to the year 2000.

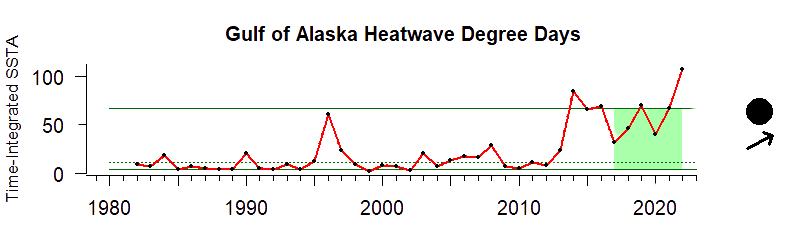

Heatwave Intensity - Gulf of Alaska

During the last five years there has been an increasing trend and the five-year average is between the 10th and 90th percentiles of all observed data in the time series.

Values indicate cumulative annual heatwave intensity and duration in a region in degree-days

Description of Time Series: This time series shows the average integrated degree day value for Alaska’s Gulf of Alaska region. During the last five years there has been an increasing trend and the five-year average is between the 10th and 90th percentiles of all observed data in the time series.

Indicator Source Information:

The marine heatwave data shown here are calculated by NOAA’s National Centers for Environmental Information using Optimum Interpolation Sea Surface Temperature (OISST) data. The NOAA 1/4° OISST is a long term Climate Data Record that incorporates observations from different platforms (satellites, ships, buoys and Argo floats) into a regular global grid. The dataset is interpolated to fill gaps on the grid and create a spatially complete map of sea surface temperature. Satellite and ship observations are referenced to buoys to compensate for platform differences and sensor biases.

Data Background and Caveats:

Heatwave metrics are calculated using OISST, a product that uses some forms of interpolation to fill data gaps. Heatwaves are defined by Hobday et al., 2016 as distinct events where SST anomaly reaches the 90th percentile in a pixel for at least 5 days, separated out by 3 or more days.

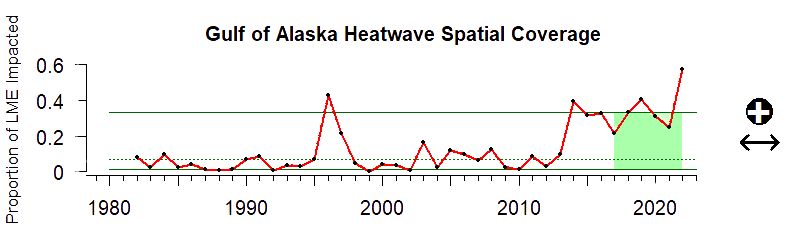

Heatwave Area - Gulf of Alaska

During the last five years there has been no trend and the five-year average is above the 90th percentile of all observed data in the time series.

Values indicate monthly percent of an LME area affected by heatwave

Description of Time Series: This time series shows the monthly heatwave spatial coverage for Alaska’s Gulf of Alaska Region. During the last five years there has been no trend and the five-year average is above the 90th percentile of all observed data in the time series.

Indicator Source Information:

The marine heatwave data shown here are calculated by NOAA’s National Centers for Environmental Information using Optimum Interpolation Sea Surface Temperature (OISST) data. The NOAA 1/4° OISST is a long term Climate Data Record that incorporates observations from different platforms (satellites, ships, buoys and Argo floats) into a regular global grid. The dataset is interpolated to fill gaps on the grid and create a spatially complete map of sea surface temperature. Satellite and ship observations are referenced to buoys to compensate for platform differences and sensor biases.

Data Background and Caveats:

Heatwave metrics are calculated using OISST, a product that uses some forms of interpolation to fill data gaps. Heatwaves are defined by Hobday et al., 2016 as distinct events where SST anomaly reaches the 90th percentile in a pixel for at least 5 days, separated out by 3 or more days

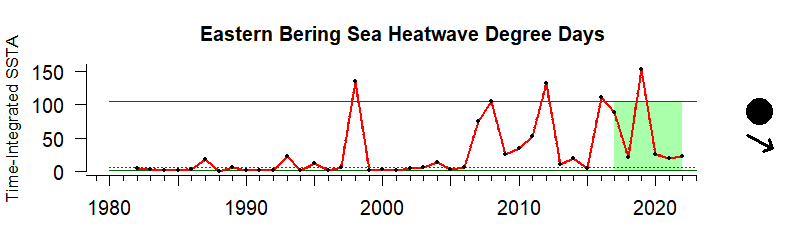

Heatwave Intensity - Eastern Bering Sea

During the last five years there has been a downward trend.

Values indicate cumulative annual heatwave intensity and duration in a region in degree-days

Description of Time Series: This time series shows the average integrated degree day value for Alaska’s Eastern Bering Sea region. During the last five years there has been a downward trend.

Indicator Source Information:

The marine heatwave data shown here are calculated by NOAA’s National Centers for Environmental Information using Optimum Interpolation Sea Surface Temperature (OISST) data. The NOAA 1/4° OISST is a long term Climate Data Record that incorporates observations from different platforms (satellites, ships, buoys and Argo floats) into a regular global grid. The dataset is interpolated to fill gaps on the grid and create a spatially complete map of sea surface temperature. Satellite and ship observations are referenced to buoys to compensate for platform differences and sensor biases.

Data Background and Caveats:

Heatwave metrics are calculated using OISST, a product that uses some forms of interpolation to fill data gaps. Heatwaves are defined by Hobday et al., 2016 as distinct events where SST anomaly reaches the 90th percentile in a pixel for at least 5 days, separated out by 3 or more days.

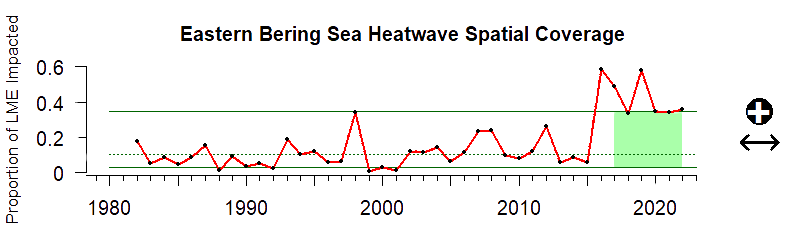

Heatwave Area - Eastern Bering Sea

During the last five years heatwave coverage has had no trend, and the five-year average is above the 90th percentile of all observed data in the time series.

Values indicate monthly percent of an LME area affected by heatwave

Description of Time Series: This time series shows the monthly heatwave spatial coverage for Alaska’s Eastern Bering Sea Region. During the last five years heatwave coverage has had no trend, and the five-year average is above the 90th percentile of all observed data in the time series.

Indicator Source Information:

The marine heatwave data shown here are calculated by NOAA’s National Centers for Environmental Information using Optimum Interpolation Sea Surface Temperature (OISST) data. The NOAA 1/4° OISST is a long term Climate Data Record that incorporates observations from different platforms (satellites, ships, buoys and Argo floats) into a regular global grid. The dataset is interpolated to fill gaps on the grid and create a spatially complete map of sea surface temperature. Satellite and ship observations are referenced to buoys to compensate for platform differences and sensor biases.

Data Background and Caveats:

Heatwave metrics are calculated using OISST, a product that uses some forms of interpolation to fill data gaps. Heatwaves are defined by Hobday et al., 2016 as distinct events where SST anomaly reaches the 90th percentile in a pixel for at least 5 days, separated out by 3 or more days

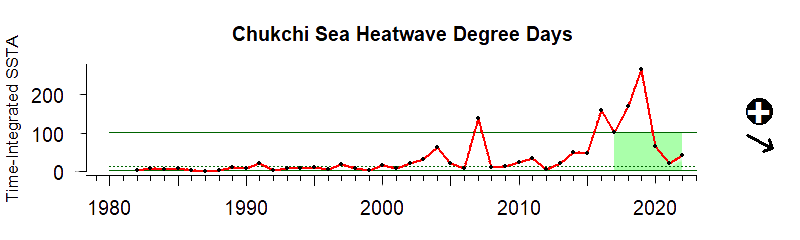

Heatwave Intensity - Chukchi Sea

During the last five years there has been a significant downward trend but the five-year average is above the 90th percentile of all observed data in the time series.

Values indicate cumulative annual heatwave intensity and duration in a region in degree-days

Description of Time Series: This time series shows the average integrated degree day value for Alaska’s Chukchi Sea region. During the last five years there has been a significant downward trend but the five-year average is above the 90th percentile of all observed data in the time series.

Indicator Source Information:

The marine heatwave data shown here are calculated by NOAA’s National Centers for Environmental Information using Optimum Interpolation Sea Surface Temperature (OISST) data. The NOAA 1/4° OISST is a long term Climate Data Record that incorporates observations from different platforms (satellites, ships, buoys and Argo floats) into a regular global grid. The dataset is interpolated to fill gaps on the grid and create a spatially complete map of sea surface temperature. Satellite and ship observations are referenced to buoys to compensate for platform differences and sensor biases.

Data Background and Caveats:

Heatwave metrics are calculated using OISST, a product that uses some forms of interpolation to fill data gaps. Heatwaves are defined by Hobday et al., 2016 as distinct events where SST anomaly reaches the 90th percentile in a pixel for at least 5 days, separated out by 3 or more days.

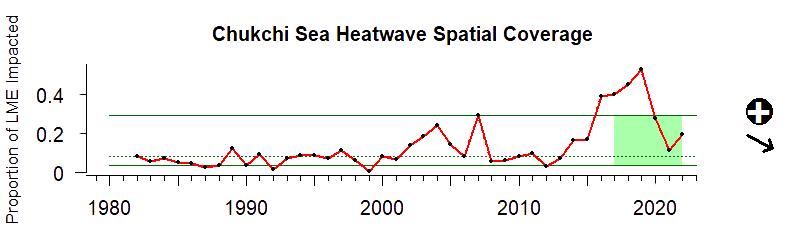

Heatwave Area - Chukchi Sea

During the last five years there has been a significant downward trend and the five-year average is above the 90th percentile of all observed data in the time series.

Values indicate monthly percent of an LME area affected by heatwave

Description of Time Series: This time series shows the monthly heatwave spatial coverage for Alaska’s Chukchi Sea Region. During the last five years there has been a significant downward trend and the five-year average is above the 90th percentile of all observed data in the time series.

Indicator Source Information:

The marine heatwave data shown here are calculated by NOAA’s National Centers for Environmental Information using Optimum Interpolation Sea Surface Temperature (OISST) data. The NOAA 1/4° OISST is a long term Climate Data Record that incorporates observations from different platforms (satellites, ships, buoys and Argo floats) into a regular global grid. The dataset is interpolated to fill gaps on the grid and create a spatially complete map of sea surface temperature. Satellite and ship observations are referenced to buoys to compensate for platform differences and sensor biases.

Data Background and Caveats:

Heatwave metrics are calculated using OISST, a product that uses some forms of interpolation to fill data gaps. Heatwaves are defined by Hobday et al., 2016 as distinct events where SST anomaly reaches the 90th percentile in a pixel for at least 5 days, separated out by 3 or more days

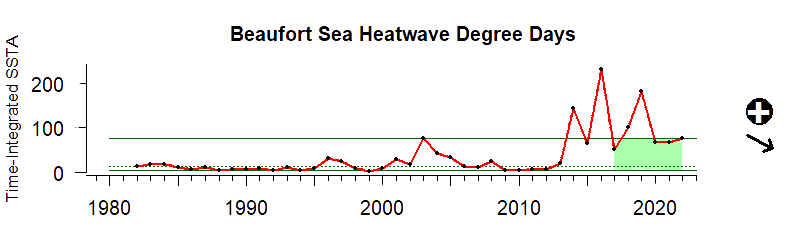

Heatwave Intensity - Beaufort Sea

During the last five years there has been a downward trend but values have been above the 90th percentile of all data.

Values indicate cumulative annual heatwave intensity and duration in a region in degree-days

Description of Time Series: This time series shows the average integrated degree day value for Alaska’s Beaufort Sea region. During the last five years there has been a downward trend but values have been above the 90th percentile of all data.

Indicator Source Information:

The marine heatwave data shown here are calculated by NOAA’s National Centers for Environmental Information using Optimum Interpolation Sea Surface Temperature (OISST) data. The NOAA 1/4° OISST is a long term Climate Data Record that incorporates observations from different platforms (satellites, ships, buoys and Argo floats) into a regular global grid. The dataset is interpolated to fill gaps on the grid and create a spatially complete map of sea surface temperature. Satellite and ship observations are referenced to buoys to compensate for platform differences and sensor biases.

Data Background and Caveats:

Heatwave metrics are calculated using OISST, a product that uses some forms of interpolation to fill data gaps. Heatwaves are defined by Hobday et al., 2016 as distinct events where SST anomaly reaches the 90th percentile in a pixel for at least 5 days, separated out by 3 or more days.

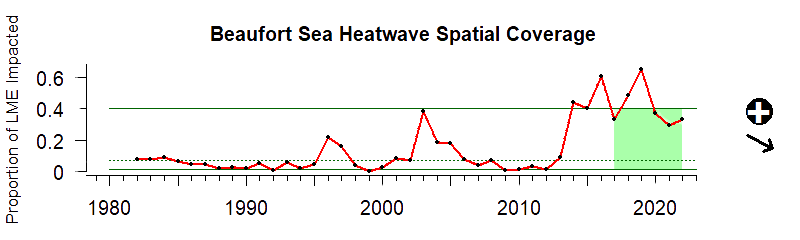

Heatwave Area - Beaufort Sea

During the last five years there has been a significant downward trend and the five-year average is above the 90th percentile of all observed data in the time series.

Values indicate monthly percent of an LME area affected by heatwave

Description of Time Series: This time series shows the monthly heatwave spatial coverage for Alaska’s Beaufort Sea Region. During the last five years there has been a significant downward trend and the five-year average is above the 90th percentile of all observed data in the time series.

Indicator Source Information:

The marine heatwave data shown here are calculated by NOAA’s National Centers for Environmental Information using Optimum Interpolation Sea Surface Temperature (OISST) data. The NOAA 1/4° OISST is a long term Climate Data Record that incorporates observations from different platforms (satellites, ships, buoys and Argo floats) into a regular global grid. The dataset is interpolated to fill gaps on the grid and create a spatially complete map of sea surface temperature. Satellite and ship observations are referenced to buoys to compensate for platform differences and sensor biases.

Data Background and Caveats:

Heatwave metrics are calculated using OISST, a product that uses some forms of interpolation to fill data gaps. Heatwaves are defined by Hobday et al., 2016 as distinct events where SST anomaly reaches the 90th percentile in a pixel for at least 5 days, separated out by 3 or more days

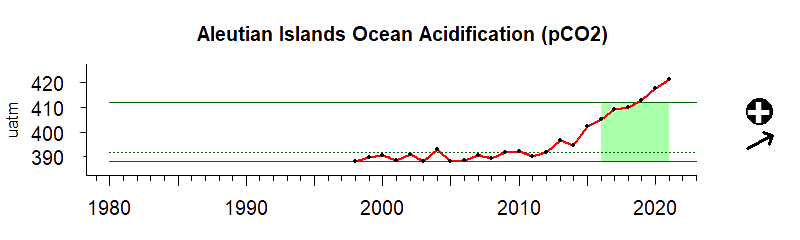

Sea Surface pCO2 - Aleutian Islands

Between 2016 and 2021 pCO2 showed a significant upward trend and was above the range of historical values.

The pCO2 data shown here as an ecosystem indicator of ocean acidification represent regional annual averages of these mapped estimates.

Description of Time Series: Between 2016 and 2021 pCO2 showed a significant upward trend and was above the range of historical values. The estimated uncertainty of the pCO2 values used to compute this regional average is ±19 μatm.

Description of Sea Surface pCO2:

Carbon dioxide (CO2) released from fossil fuel burning and other human activities (also known as “anthropogenic CO2”) not only accumulates in Earth’s atmosphere, but is also absorbed by seawater at the ocean surface. This process represents a double-edged sword for the planet: CO2, which has negative consequences for climate change, is removed from the atmosphere but it also contributes to the acidification of ocean waters, which can harm sea life like corals and crabs. The partial pressure of CO2 in seawater (pCO2) represents the relative amount of CO2 in the water. It is a critical metric for calculating the exchange of CO2 across the air–sea interface and for tracking the effects of anthropogenic carbon on surface ocean chemistry.

Data Source:

Global observations of pCO2 from automated shipboard systems that take in and analyze water while a vessel is moving are aggregated in the Surface Ocean CO2 Atlas (SOCAT; Bakker et al., 2016). These shipboard observations have been combined with data from available observational, model-based, and satellite products (e.g., sea-surface temperature, salinity, and wind speed) to create estimates of surface ocean pCO2 in U.S. Large Marine Ecosystems over multiple decades, using a technique known as machine learning (Sharp et al., in prep.). The pCO2 data shown here as an ecosystem indicator of ocean acidification represent regional annual averages of these mapped estimates. Uncertainty in pCO2 is estimated from a data-based validation of the machine-learning algorithms for each Large Marine Ecosystem, scaled by the data coverage in a given month.

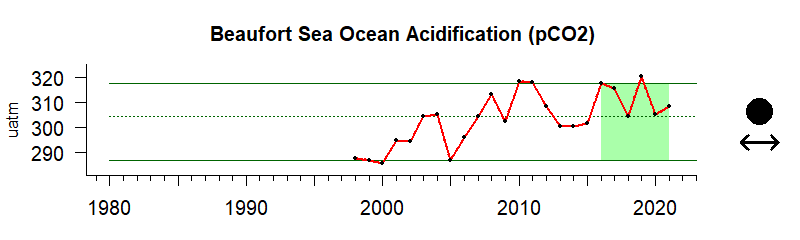

Sea Surafce pCO2 - Beaufort Sea

Between 2016 and 2021 pCO2 showed no significant trend and was similar to historical values.

The pCO2 data shown here as an ecosystem indicator of ocean acidification represent regional annual averages of these mapped estimates.

Description of Time Series: Between 2016 and 2021 pCO2 showed no significant trend and was similar to historical values. The estimated uncertainty of the pCO2 values used to compute this regional average is ±60 μatm.

Description of Sea Surface pCO2:

Carbon dioxide (CO2) released from fossil fuel burning and other human activities (also known as “anthropogenic CO2”) not only accumulates in Earth’s atmosphere, but is also absorbed by seawater at the ocean surface. This process represents a double-edged sword for the planet: CO2, which has negative consequences for climate change, is removed from the atmosphere but it also contributes to the acidification of ocean waters, which can harm sea life like corals and crabs. The partial pressure of CO2 in seawater (pCO2) represents the relative amount of CO2 in the water. It is a critical metric for calculating the exchange of CO2 across the air–sea interface and for tracking the effects of anthropogenic carbon on surface ocean chemistry.

Data Source:

Global observations of pCO2 from automated shipboard systems that take in and analyze water while a vessel is moving are aggregated in the Surface Ocean CO2 Atlas (SOCAT; Bakker et al., 2016). These shipboard observations have been combined with data from available observational, model-based, and satellite products (e.g., sea-surface temperature, salinity, and wind speed) to create estimates of surface ocean pCO2 in U.S. Large Marine Ecosystems over multiple decades, using a technique known as machine learning (Sharp et al., in prep.). The pCO2 data shown here as an ecosystem indicator of ocean acidification represent regional annual averages of these mapped estimates. Uncertainty in pCO2 is estimated from a data-based validation of the machine-learning algorithms for each Large Marine Ecosystem, scaled by the data coverage in a given month.

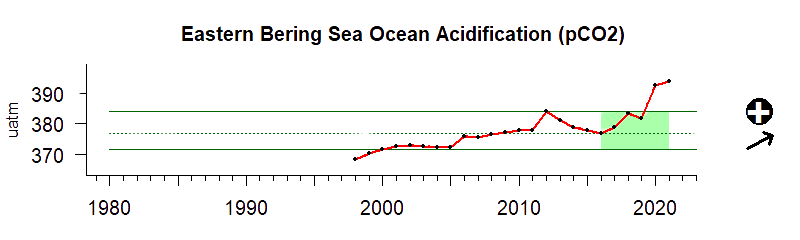

Sea Surface pCO2 - Eastern Bering Sea

Between 2016 and 2021 pCO2 showed a significant increasing trend and was above historical values.

The pCO2 data shown here as an ecosystem indicator of ocean acidification represent regional annual averages of these mapped estimates.

Description of Time Series: Between 2016 and 2021 pCO2 showed a significant increasing trend and was above historical values. The estimated uncertainty of the pCO2 values used to compute this regional average is ±16 μatm.

Description of Sea Surface pCO2:

Carbon dioxide (CO2) released from fossil fuel burning and other human activities (also known as “anthropogenic CO2”) not only accumulates in Earth’s atmosphere, but is also absorbed by seawater at the ocean surface. This process represents a double-edged sword for the planet: CO2, which has negative consequences for climate change, is removed from the atmosphere but it also contributes to the acidification of ocean waters, which can harm sea life like corals and crabs. The partial pressure of CO2 in seawater (pCO2) represents the relative amount of CO2 in the water. It is a critical metric for calculating the exchange of CO2 across the air–sea interface and for tracking the effects of anthropogenic carbon on surface ocean chemistry.

Data Source:

Global observations of pCO2 from automated shipboard systems that take in and analyze water while a vessel is moving are aggregated in the Surface Ocean CO2 Atlas (SOCAT; Bakker et al., 2016). These shipboard observations have been combined with data from available observational, model-based, and satellite products (e.g., sea-surface temperature, salinity, and wind speed) to create estimates of surface ocean pCO2 in U.S. Large Marine Ecosystems over multiple decades, using a technique known as machine learning (Sharp et al., in prep.). The pCO2 data shown here as an ecosystem indicator of ocean acidification represent regional annual averages of these mapped estimates. Uncertainty in pCO2 is estimated from a data-based validation of the machine-learning algorithms for each Large Marine Ecosystem, scaled by the data coverage in a given month.

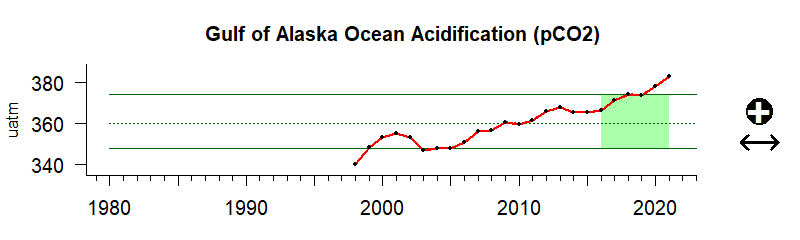

Sea Surface pCO2 - Gulf of Alaska

Between 2016 and 2021 pCO2 showed no significant trend and was above historical values.

The pCO2 data shown here as an ecosystem indicator of ocean acidification represent regional annual averages of these mapped estimates.

Description of Time Series: Between 2016 and 2021 pCO2 showed no significant trend and was above historical values. The estimated uncertainty of the pCO2 values used to compute this regional average is ±23 μatm.

Description of Sea Surface pCO2:

Carbon dioxide (CO2) released from fossil fuel burning and other human activities (also known as “anthropogenic CO2”) not only accumulates in Earth’s atmosphere, but is also absorbed by seawater at the ocean surface. This process represents a double-edged sword for the planet: CO2, which has negative consequences for climate change, is removed from the atmosphere but it also contributes to the acidification of ocean waters, which can harm sea life like corals and crabs. The partial pressure of CO2 in seawater (pCO2) represents the relative amount of CO2 in the water. It is a critical metric for calculating the exchange of CO2 across the air–sea interface and for tracking the effects of anthropogenic carbon on surface ocean chemistry.

Data Source:

Global observations of pCO2 from automated shipboard systems that take in and analyze water while a vessel is moving are aggregated in the Surface Ocean CO2 Atlas (SOCAT; Bakker et al., 2016). These shipboard observations have been combined with data from available observational, model-based, and satellite products (e.g., sea-surface temperature, salinity, and wind speed) to create estimates of surface ocean pCO2 in U.S. Large Marine Ecosystems over multiple decades, using a technique known as machine learning (Sharp et al., in prep.). The pCO2 data shown here as an ecosystem indicator of ocean acidification represent regional annual averages of these mapped estimates. Uncertainty in pCO2 is estimated from a data-based validation of the machine-learning algorithms for each Large Marine Ecosystem, scaled by the data coverage in a given month.

Close

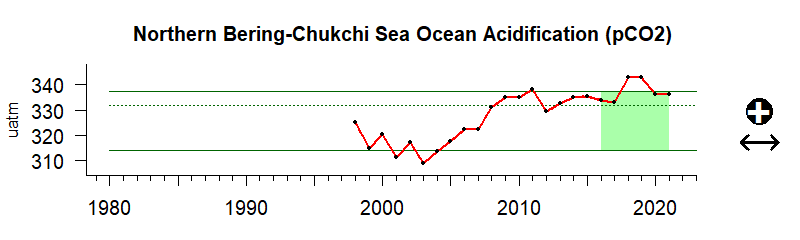

Sea Surface pCO2 - Northern Bering and Chukchi Seas

Between 2016 and 2021 pCO2 showed no significant trend and was above historical values.

The pCO2 data shown here as an ecosystem indicator of ocean acidification represent regional annual averages of these mapped estimates.

Description of Time Series: Between 2016 and 2021 pCO2 showed no significant trend and was above historical values. The estimated uncertainty of the pCO2 values used to compute this regional average is ±60 μatm.

Description of Sea Surface pCO2:

Carbon dioxide (CO2) released from fossil fuel burning and other human activities (also known as “anthropogenic CO2”) not only accumulates in Earth’s atmosphere, but is also absorbed by seawater at the ocean surface. This process represents a double-edged sword for the planet: CO2, which has negative consequences for climate change, is removed from the atmosphere but it also contributes to the acidification of ocean waters, which can harm sea life like corals and crabs. The partial pressure of CO2 in seawater (pCO2) represents the relative amount of CO2 in the water. It is a critical metric for calculating the exchange of CO2 across the air–sea interface and for tracking the effects of anthropogenic carbon on surface ocean chemistry.

Data Source:

Global observations of pCO2 from automated shipboard systems that take in and analyze water while a vessel is moving are aggregated in the Surface Ocean CO2 Atlas (SOCAT; Bakker et al., 2016). These shipboard observations have been combined with data from available observational, model-based, and satellite products (e.g., sea-surface temperature, salinity, and wind speed) to create estimates of surface ocean pCO2 in U.S. Large Marine Ecosystems over multiple decades, using a technique known as machine learning (Sharp et al., in prep.). The pCO2 data shown here as an ecosystem indicator of ocean acidification represent regional annual averages of these mapped estimates. Uncertainty in pCO2 is estimated from a data-based validation of the machine-learning algorithms for each Large Marine Ecosystem, scaled by the data coverage in a given month.

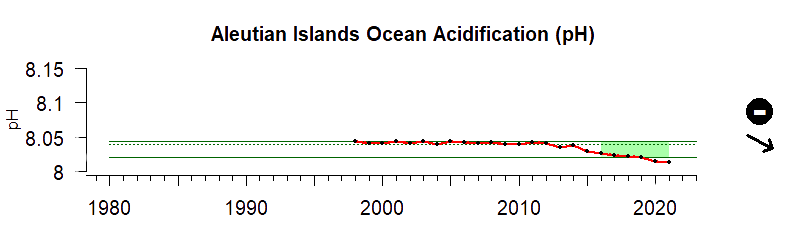

Sea Surface pH - Aleutian Islands

Between 2016 and 2021 pH showed a small downward trend and was below historical values.

The pH data shown here as an ecosystem indicator of ocean acidification represent regional annual averages of these estimates.

Description of Time Series: Between 2016 and 2021 pH showed a small downward trend and was below historical values.

Description of Sea Surface pH:

Man-made (or “anthropogenic”) CO2 that is taken up by the ocean influences the chemistry of seawater, resulting in an increase in hydrogen ion concentration of the surface ocean (i.e. a decrease in surface ocean pH). pH can be viewed as a “master variable” in ocean chemistry, controlling acid-base balance in the sea. It is also a common way to quantify ocean acidification: average surface ocean pH has decreased by more than 0.1 units since the beginning of the industrial revolution (Jiang et al., 2023).

Data Source:

Mapped estimates of surface-ocean pCO2 in U.S. Large Marine Ecosystems (LME’s) (Sharp et al., in prep.), based on observations from the SOCAT database, have been paired with another key ocean-carbon variable called total alkalinity (TA), estimated from salinity, temperature, and spatial information using algorithms called ESPERs (Carter et al., 2021), to calculate surface ocean pH across the U.S. LME’s. The pH data shown here as an ecosystem indicator of ocean acidification represent regional annual averages of these estimates. Uncertainty in pH is determined by propagating pCO2 and TA uncertainties through calculations, using reasonable estimates of uncertainty in required chemical constants and ancillary variables.

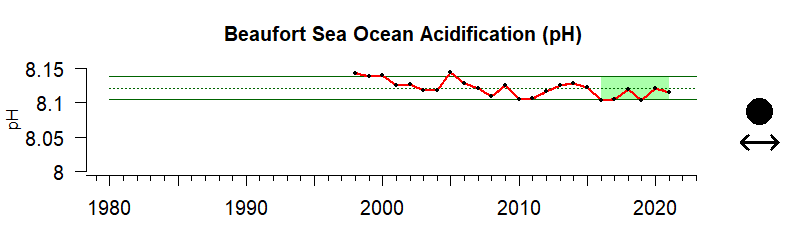

Sea Surface pH - Beaufort Sea

Between 2016 and 2021 pH showed no significant trend and was similar to historical values.

The pH data shown here as an ecosystem indicator of ocean acidification represent regional annual averages of these estimates.

Description of Time Series: Between 2016 and 2021 pH showed no significant trend and was similar to historical values.

Description of Sea Surface pH:

Man-made (or “anthropogenic”) CO2 that is taken up by the ocean influences the chemistry of seawater, resulting in an increase in hydrogen ion concentration of the surface ocean (i.e. a decrease in surface ocean pH). pH can be viewed as a “master variable” in ocean chemistry, controlling acid-base balance in the sea. It is also a common way to quantify ocean acidification: average surface ocean pH has decreased by more than 0.1 units since the beginning of the industrial revolution (Jiang et al., 2023).

Data Source:

Mapped estimates of surface-ocean pCO2 in U.S. Large Marine Ecosystems (LME’s) (Sharp et al., in prep.), based on observations from the SOCAT database, have been paired with another key ocean-carbon variable called total alkalinity (TA), estimated from salinity, temperature, and spatial information using algorithms called ESPERs (Carter et al., 2021), to calculate surface ocean pH across the U.S. LME’s. The pH data shown here as an ecosystem indicator of ocean acidification represent regional annual averages of these estimates. Uncertainty in pH is determined by propagating pCO2 and TA uncertainties through calculations, using reasonable estimates of uncertainty in required chemical constants and ancillary variables.

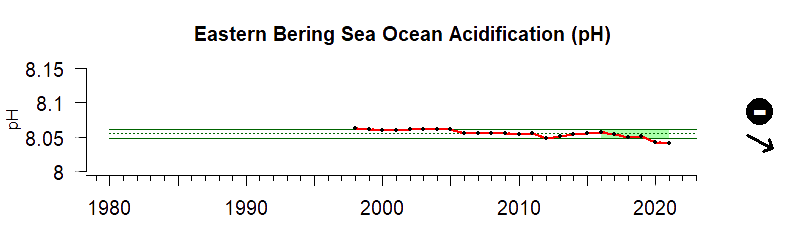

Sea Surface pH - Eastern Bering Sea

Between 2016 and 2021 pH showed a significant decreasing trend and was below historical values.

The pH data shown here as an ecosystem indicator of ocean acidification represent regional annual averages of these estimates.

Description of Time Series: Between 2016 and 2021 pH showed a significant decreasing trend and was below historical values.

Description of Sea Surface pH:

Man-made (or “anthropogenic”) CO2 that is taken up by the ocean influences the chemistry of seawater, resulting in an increase in hydrogen ion concentration of the surface ocean (i.e. a decrease in surface ocean pH). pH can be viewed as a “master variable” in ocean chemistry, controlling acid-base balance in the sea. It is also a common way to quantify ocean acidification: average surface ocean pH has decreased by more than 0.1 units since the beginning of the industrial revolution (Jiang et al., 2023).

Data Source:

Mapped estimates of surface-ocean pCO2 in U.S. Large Marine Ecosystems (LME’s) (Sharp et al., in prep.), based on observations from the SOCAT database, have been paired with another key ocean-carbon variable called total alkalinity (TA), estimated from salinity, temperature, and spatial information using algorithms called ESPERs (Carter et al., 2021), to calculate surface ocean pH across the U.S. LME’s. The pH data shown here as an ecosystem indicator of ocean acidification represent regional annual averages of these estimates. Uncertainty in pH is determined by propagating pCO2 and TA uncertainties through calculations, using reasonable estimates of uncertainty in required chemical constants and ancillary variables.

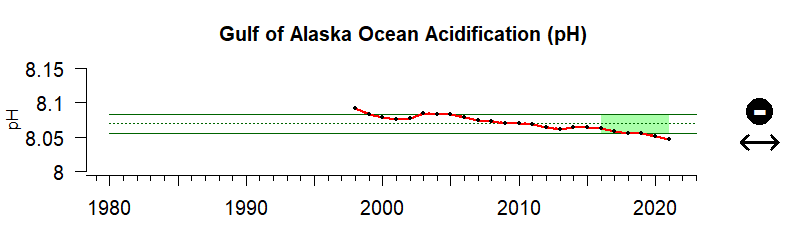

Sea Surface pH - Gulf of Alaska

Between 2016 and 2021 pH showed no significant trend and was below historical values.

The pH data shown here as an ecosystem indicator of ocean acidification represent regional annual averages of these estimates.

Description of Time Series: Between 2016 and 2021 pH showed no significant trend and was below historical values.

Description of Sea Surface pH:

Man-made (or “anthropogenic”) CO2 that is taken up by the ocean influences the chemistry of seawater, resulting in an increase in hydrogen ion concentration of the surface ocean (i.e. a decrease in surface ocean pH). pH can be viewed as a “master variable” in ocean chemistry, controlling acid-base balance in the sea. It is also a common way to quantify ocean acidification: average surface ocean pH has decreased by more than 0.1 units since the beginning of the industrial revolution (Jiang et al., 2023).

Data Source:

Mapped estimates of surface-ocean pCO2 in U.S. Large Marine Ecosystems (LME’s) (Sharp et al., in prep.), based on observations from the SOCAT database, have been paired with another key ocean-carbon variable called total alkalinity (TA), estimated from salinity, temperature, and spatial information using algorithms called ESPERs (Carter et al., 2021), to calculate surface ocean pH across the U.S. LME’s. The pH data shown here as an ecosystem indicator of ocean acidification represent regional annual averages of these estimates. Uncertainty in pH is determined by propagating pCO2 and TA uncertainties through calculations, using reasonable estimates of uncertainty in required chemical constants and ancillary variables.

Close

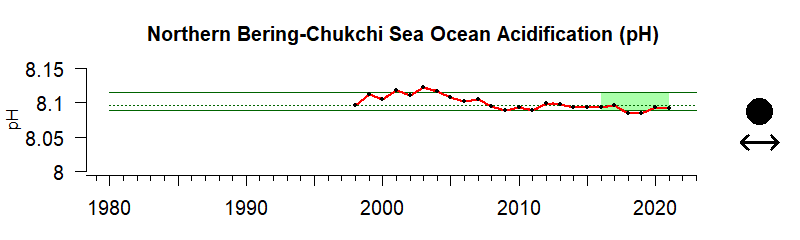

Sea Surface pH - Northern Bering and Chukchi Seas

Between 2016 and 2021 pH showed no significant trend and was similar to historical values.

The pH data shown here as an ecosystem indicator of ocean acidification represent regional annual averages of these estimates.

Description of Time Series: Between 2016 and 2021 pH showed no significant trend and was similar to historical values.

Description of Sea Surface pH:

Man-made (or “anthropogenic”) CO2 that is taken up by the ocean influences the chemistry of seawater, resulting in an increase in hydrogen ion concentration of the surface ocean (i.e. a decrease in surface ocean pH). pH can be viewed as a “master variable” in ocean chemistry, controlling acid-base balance in the sea. It is also a common way to quantify ocean acidification: average surface ocean pH has decreased by more than 0.1 units since the beginning of the industrial revolution (Jiang et al., 2023).

Data Source:

Mapped estimates of surface-ocean pCO2 in U.S. Large Marine Ecosystems (LME’s) (Sharp et al., in prep.), based on observations from the SOCAT database, have been paired with another key ocean-carbon variable called total alkalinity (TA), estimated from salinity, temperature, and spatial information using algorithms called ESPERs (Carter et al., 2021), to calculate surface ocean pH across the U.S. LME’s. The pH data shown here as an ecosystem indicator of ocean acidification represent regional annual averages of these estimates. Uncertainty in pH is determined by propagating pCO2 and TA uncertainties through calculations, using reasonable estimates of uncertainty in required chemical constants and ancillary variables.

Close

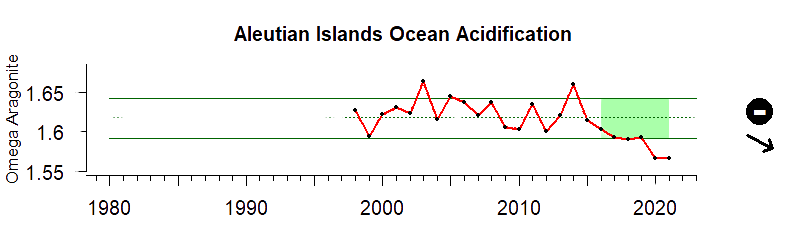

Sea Surface Ωar - Aleutian Islands

Between 2016 and 2021 Sea Surface Ωar showed a significant decreasing trend and was lower than historical values.

The Ωar data shown here as an ecosystem indicator of ocean acidification represent regional averages of these estimates.

Description of Time Series: Between 2016 and 2021 Sea Surface Ωar showed a significant decreasing trend and was lower than historical values.

Description of Sea Surface Ωar:

Many marine animals and plants build shells or other hard parts from the minerals aragonite and calcite, which are forms of the chemical compound calcium carbonate. The chemical building blocks of these minerals are calcium and carbonate ions, which are common constituents of seawater. However, one effect of ocean acidification is to reduce the carbonate ion concentration in seawater, making it more difficult for these minerals to form. The chemical expression that describes the tendency of these minerals to form at equilibrium is called the saturation state of that mineral: higher values support mineral formation, while lower values inhibit mineral formation, or even promote the dissolution of these minerals. We present here saturation-state estimates for the mineral aragonite (Ωar), which is used by many marine organisms including corals, mollusks, and some zooplankton to create hard parts. At 20°C, saturation state of the mineral calcite is about 50% higher than aragonite (Mucci, 1983)

Data Source:

Mapped estimates of surface-ocean pCO2 in U.S. Large Marine Ecosystems (LME’s) (Sharp et al., in prep.), based on observations from the SOCAT database, have been paired with another key ocean-carbon variable called total alkalinity (TA), estimated from salinity, temperature, and spatial information using algorithms called ESPERs (Carter et al., 2021), to calculate surface-ocean Ωar across the U.S. LME’s. The Ωar data shown here as an ecosystem indicator of ocean acidification represent regional averages of these estimates. Uncertainty in Ωar is determined by propagating pCO2 and TA uncertainties through calculations, using reasonable estimates of uncertainty in required chemical constants and ancillary variables.

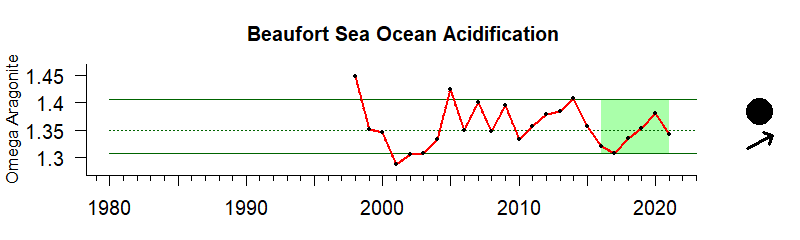

Sea Surface Ωar - Beaufort Sea

Between 2016 and 2021 Sea Surface Ωar showed no significant trend and was similar to historical values.

The Ωar data shown here as an ecosystem indicator of ocean acidification represent regional averages of these estimates.

Description of Time Series: Between 2016 and 2021 Sea Surface Ωar showed no significant trend and was similar to historical values.

Description of Sea Surface Ωar:

Many marine animals and plants build shells or other hard parts from the minerals aragonite and calcite, which are forms of the chemical compound calcium carbonate. The chemical building blocks of these minerals are calcium and carbonate ions, which are common constituents of seawater. However, one effect of ocean acidification is to reduce the carbonate ion concentration in seawater, making it more difficult for these minerals to form. The chemical expression that describes the tendency of these minerals to form at equilibrium is called the saturation state of that mineral: higher values support mineral formation, while lower values inhibit mineral formation, or even promote the dissolution of these minerals. We present here saturation-state estimates for the mineral aragonite (Ωar), which is used by many marine organisms including corals, mollusks, and some zooplankton to create hard parts. At 20°C, saturation state of the mineral calcite is about 50% higher than aragonite (Mucci, 1983)

Data Source:

Mapped estimates of surface-ocean pCO2 in U.S. Large Marine Ecosystems (LME’s) (Sharp et al., in prep.), based on observations from the SOCAT database, have been paired with another key ocean-carbon variable called total alkalinity (TA), estimated from salinity, temperature, and spatial information using algorithms called ESPERs (Carter et al., 2021), to calculate surface-ocean Ωar across the U.S. LME’s. The Ωar data shown here as an ecosystem indicator of ocean acidification represent regional averages of these estimates. Uncertainty in Ωar is determined by propagating pCO2 and TA uncertainties through calculations, using reasonable estimates of uncertainty in required chemical constants and ancillary variables.

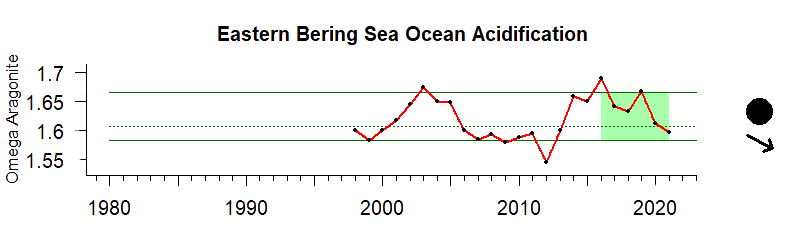

Sea Surface Ωar - Eastern Bering Sea

Between 2016 and 2021 Sea Surface Ωar showed no significant trend and was similar to historical values.

The Ωar data shown here as an ecosystem indicator of ocean acidification represent regional averages of these estimates.

Description of Time Series: Between 2016 and 2021 Sea Surface Ωar showed no significant trend and was similar to historical values.

Description of Sea Surface Ωar:

Many marine animals and plants build shells or other hard parts from the minerals aragonite and calcite, which are forms of the chemical compound calcium carbonate. The chemical building blocks of these minerals are calcium and carbonate ions, which are common constituents of seawater. However, one effect of ocean acidification is to reduce the carbonate ion concentration in seawater, making it more difficult for these minerals to form. The chemical expression that describes the tendency of these minerals to form at equilibrium is called the saturation state of that mineral: higher values support mineral formation, while lower values inhibit mineral formation, or even promote the dissolution of these minerals. We present here saturation-state estimates for the mineral aragonite (Ωar), which is used by many marine organisms including corals, mollusks, and some zooplankton to create hard parts. At 20°C, saturation state of the mineral calcite is about 50% higher than aragonite (Mucci, 1983)

Data Source:

Mapped estimates of surface-ocean pCO2 in U.S. Large Marine Ecosystems (LME’s) (Sharp et al., in prep.), based on observations from the SOCAT database, have been paired with another key ocean-carbon variable called total alkalinity (TA), estimated from salinity, temperature, and spatial information using algorithms called ESPERs (Carter et al., 2021), to calculate surface-ocean Ωar across the U.S. LME’s. The Ωar data shown here as an ecosystem indicator of ocean acidification represent regional averages of these estimates. Uncertainty in Ωar is determined by propagating pCO2 and TA uncertainties through calculations, using reasonable estimates of uncertainty in required chemical constants and ancillary variables.

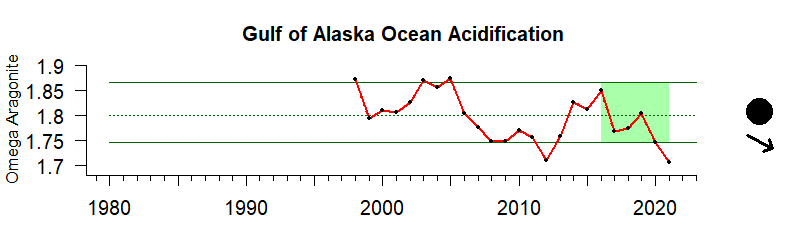

Sea Surface Ωar - Gulf of Alaska

Between 2016 and 2021 Sea Surface Ωar showed a significant downward trend and was similar to historical values.

The Ωar data shown here as an ecosystem indicator of ocean acidification represent regional averages of these estimates.

Description of Time Series: Between 2016 and 2021 Sea Surface Ωar showed a significant downward trend and was similar to historical values.

Description of Sea Surface Ωar:

Many marine animals and plants build shells or other hard parts from the minerals aragonite and calcite, which are forms of the chemical compound calcium carbonate. The chemical building blocks of these minerals are calcium and carbonate ions, which are common constituents of seawater. However, one effect of ocean acidification is to reduce the carbonate ion concentration in seawater, making it more difficult for these minerals to form. The chemical expression that describes the tendency of these minerals to form at equilibrium is called the saturation state of that mineral: higher values support mineral formation, while lower values inhibit mineral formation, or even promote the dissolution of these minerals. We present here saturation-state estimates for the mineral aragonite (Ωar), which is used by many marine organisms including corals, mollusks, and some zooplankton to create hard parts. At 20°C, saturation state of the mineral calcite is about 50% higher than aragonite (Mucci, 1983)

Data Source:

Mapped estimates of surface-ocean pCO2 in U.S. Large Marine Ecosystems (LME’s) (Sharp et al., in prep.), based on observations from the SOCAT database, have been paired with another key ocean-carbon variable called total alkalinity (TA), estimated from salinity, temperature, and spatial information using algorithms called ESPERs (Carter et al., 2021), to calculate surface-ocean Ωar across the U.S. LME’s. The Ωar data shown here as an ecosystem indicator of ocean acidification represent regional averages of these estimates. Uncertainty in Ωar is determined by propagating pCO2 and TA uncertainties through calculations, using reasonable estimates of uncertainty in required chemical constants and ancillary variables.

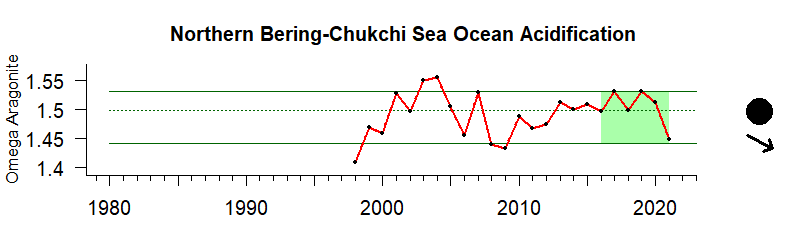

Sea Surface Ωar - Northern Bering and Chukchi Seas

Between 2016 and 2021 Sea Surface Ωar showed a significant downward trend and was similar to historical values.

The Ωar data shown here as an ecosystem indicator of ocean acidification represent regional averages of these estimates.

Description of Time Series: Between 2016 and 2021 Sea Surface Ωar showed a significant downward trend and was similar to historical values.

Description of Sea Surface Ωar:

Many marine animals and plants build shells or other hard parts from the minerals aragonite and calcite, which are forms of the chemical compound calcium carbonate. The chemical building blocks of these minerals are calcium and carbonate ions, which are common constituents of seawater. However, one effect of ocean acidification is to reduce the carbonate ion concentration in seawater, making it more difficult for these minerals to form. The chemical expression that describes the tendency of these minerals to form at equilibrium is called the saturation state of that mineral: higher values support mineral formation, while lower values inhibit mineral formation, or even promote the dissolution of these minerals. We present here saturation-state estimates for the mineral aragonite (Ωar), which is used by many marine organisms including corals, mollusks, and some zooplankton to create hard parts. At 20°C, saturation state of the mineral calcite is about 50% higher than aragonite (Mucci, 1983)

Data Source:

Mapped estimates of surface-ocean pCO2 in U.S. Large Marine Ecosystems (LME’s) (Sharp et al., in prep.), based on observations from the SOCAT database, have been paired with another key ocean-carbon variable called total alkalinity (TA), estimated from salinity, temperature, and spatial information using algorithms called ESPERs (Carter et al., 2021), to calculate surface-ocean Ωar across the U.S. LME’s. The Ωar data shown here as an ecosystem indicator of ocean acidification represent regional averages of these estimates. Uncertainty in Ωar is determined by propagating pCO2 and TA uncertainties through calculations, using reasonable estimates of uncertainty in required chemical constants and ancillary variables.

Chlorophyll-a

During the last five years there has been a significant increasing trend while values have remained within the 10th and 90th percentiles of all observed data in the time series.

This time series shows the average concentration levels of chlorophyll a for Alaska. During the last five years there has been a significant increasing trend while values have remained within the 10th and 90th percentiles of all observed data in the time series.

Indicator and source information:

Chlorophyll-a concentration values for this indicator were obtained using data from the European Spatial Agency (ESA) that is a validated, error-characterized, Essential Climate Variable (ECV) and climate data record (CDR) from satellite observations specifically developed for climate studies. The dataset (v56.0) is created by bandshifting the reflectances values from SeaWiFS, MODIS and VIIRS to MERIS wavebands if necessary, and SeaWiFS and MODIS were corrected for inter-sensor bias when compared with MERIS in the 2003-2007 period. VIIRS and OLCI were also corrected to MERIS levels, via a two-stage process comparing against the MODIS-corrected-to-MERIS-levels (2012-2013 for VIIRS and 2016-2019 for OLCI).

Source: https://climate.esa.int/en/projects/ocean-colour/key-documents/

https://docs.pml.space/share/s/fzNSPb4aQaSDvO7xBNOCIw

Annual means for each LME were calculated from the average of the 12 monthly means in that year on a pixel by pixel basis. Then for each year, the median average was taken spatially to yield one value per year per LME. The overall “National Annual Mean” mean was calculated as the average of all LME annual means. See the Data Background section for more details.

Data background and limitations:

Satellite chlorophyll a data was extracted for each LME from the ESA OC-CCI v6.0 product. These 4 km mapped, monthly composited data were - averaged over each year to produce pixel by pixel annual composites, then the spatial median was calculated for each LME, resulting in one value per year per LME. This technique was used for each LME from North America and Hawaii. The overall “National Annual Mean” was calculated as the average of all the LME annual means. Phytoplankton concentrations are highly variable (spatially and temporally), largely driven by changing oceanographic conditions and seasonal variability.

The northern section of the Alaska region (northern Chukchi and Beaufort Sea), have no to very low data coverage for part of year, so this likely biases the absolute values for the whole region. This does not likely affect the trend.

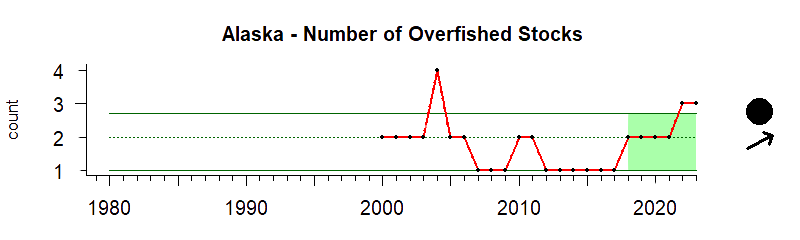

Overfished Stocks

Between 2018 and 2023 the number of overfished stocks showed an upward trend.

The x-axis represents years. The y-axis represents the number of fish stocks or fish populations that are deemed by NOAA as overfished. Overfished means the population of fish is too low. Therefore the population cannot support a large amount of fishing.

Description of time series:

The series shows the number of fish populations that have been listed as overfished since 2000. Between 2018 and 2023 the number of overfished stocks showed an upward trend.

Description of Overfished stocks:

An overfished stock is a population of fish that is too low. A stock that is experiencing overfishing has an annual rate of catch that is too high. Therefore the population cannot support that level of fishing and is below that level is deemed “overfished.” A fish population can be “overfished” as the result of many factors, including overfishing, as well as habitat degradation, pollution, climate change, and disease. The Magnuson-Stevens Act mandates that overfished stocks and stocks experiencing overfishing be reported annually. Stock status is determined by NOAA, based on the results of stock assessments.

Data Source:

Data were obtained from the NOAA Fisheries Fishery Stock Status website. Stocks that met the criteria for overfished status were summed by year for each region.

Endangered Species Act Threatened or Endangered Marine Mammals

Gauge and Trend Analyses were not appropriate for marine mammal data.

Values Correspond to the Number of ESA Threatened or Endangered Species in a given region

Data Interpretation

Gauge and Trend Analyses were not appropriate for marine mammal data.

Description of Threatened and Endangered Marine Mammals (ESA):

NOAA Fisheries is responsible for the protection, conservation, and recovery of endangered and threatened marine and anadromous species under the Endangered Species Act (ESA). The ESA aims to conserve these species and the ecosystems they depend on. Under the ESA, a species is considered endangered if it is in danger of extinction throughout all or a significant portion of its range, or threatened if it is likely to become endangered in the foreseeable future throughout all or a significant portion of its range See a species directory of all the threatened and endangered marine species under NOAA Fisheries jurisdiction, including marine mammals.

Under the ESA, a species must be listed if it is threatened or endangered because of any of the following 5 factors:

1) Present or threatened destruction, modification, or curtailment of its habitat or range;

2) Over-utilization of the species for commercial, recreational, scientific, or educational purposes;

3) Disease or predation;

4) Inadequacy of existing regulatory mechanisms; and

5) Other natural or manmade factors affecting its continued existence.

The ESA requires that listing determinations be based solely on the best scientific and commercial information available; economic impacts are not considered in making species listing determinations and are prohibited under the ESA. There are two ways by which a species may come to be listed (or delisted) under the ESA:

- NOAA Fisheries receives a petition from a person or organization requesting that NOAA lists a species as threatened or endangered, reclassify a species, or delist a species.

- NOAA Fisheries voluntarily chooses to examine the status of a species by initiating a status review of a species.

Data Background and Caveats

NOAA Fisheries goes through required regulatory steps to list, reclassify, or delist a species under the ESA. For more information, see a step-by-step description of the ESA listing process. The listing process requires time and resources; as a result, the timing and number of listed marine species is not necessarily indicative of the actual number of currently endangered or threatened species and the exact timing of when these species became eligible to be listed under the ESA. Many marine species were initially listed when the ESA was passed in 1973; others have taken more time to be listed, and some have been reclassified or delisted since then.

Close

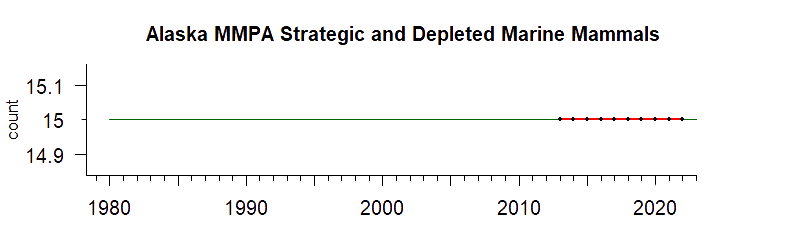

Marine Mammal Protection Act Strategic/Depleted Marine Mammal Stocks

Gauge and Trend Analyses were not appropriate for marine mammal data.

Values correspond to the number of MMPA Strategic or Depleted Marine Mammal Species listed each year in each region

Data Interpretation

Gauge and Trend Analyses were not appropriate for marine mammal data.

Description of Marine Mammal Strategic and Depleted Stocks (MMPA):

A stock is defined by the Marine Mammal Protection Act (MMPA), as a group of marine mammals of the same species or smaller taxa in a common spatial arrangement, that interbreed when mature. See a list of the marine mammal stocks NOAA protects under the MMPA.

A strategic stock is defined by the MMPA as a marine mammal stock—

- For which the level of direct human-caused mortality exceeds the potential biological removal level or PBR (defined by the MMPA as the maximum number of animals, not including natural mortalities, that may be removed from a marine mammal stock while allowing that stock to reach or maintain its optimum sustainable population);

- Which, based on the best available scientific information, is declining and is likely to be listed as a threatened species under the Endangered Species Act (ESA) within the foreseeable future; or

- Which is listed as a threatened or endangered species under the ESA, or is designated as depleted under the MMPA.

A depleted stock is defined by the MMPA as any case in which—

- The Secretary of Commerce, after consultation with the Marine Mammal Commission and the Committee of Scientific Advisors on Marine Mammals established under MMPA title II, determines that a species or population stock is below its optimum sustainable population;

- A State, to which authority for the conservation and management of a species or population stock is transferred under section 109, determines that such species or stock is below its optimum sustainable population; or

- A species or population stock is listed as an endangered species or a threatened species under the ESA.

Data Background and Caveats

NOAA Fisheries prepares marine mammal stock assessment reports to track the status of marine mammal stocks. Some marine mammal stocks are thriving, while others are declining, and we often don’t know all the reasons behind a species or stock’s population trend. Because of this variability, it is difficult to indicate the state of an ecosystem or specific region using stock assessment data for marine mammal species that often range across multiple ecosystems and regions.

Close

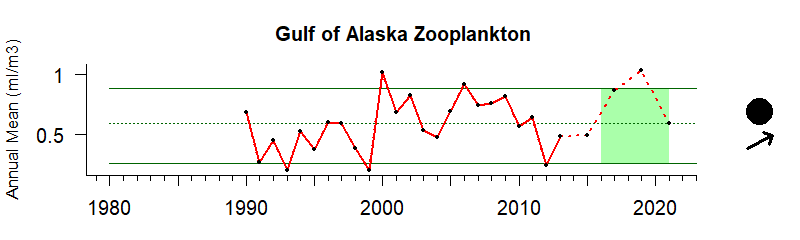

Zooplankton - Gulf of Alaska

Between 2016 and 2021 the average concentration of zooplankton biomass showed a significant increasing trend but was similar to historical values.

Description of time series:

Between 2016 and 2021 the average concentration of zooplankton biomass showed a significant increasing trend but was similar to historical values.

Indicator information

Zooplankton data for each region were obtained from the NOAA Fisheries Coastal & Oceanic Plankton Ecology, Production, & Observations Database, an integrated data set of quality-controlled, globally distributed plankton biomass and abundance data with common biomass units and served in a common electronic format with supporting documentation and access software. Alaska specific data comes from the Ecosystems and Fisheries-Oceanography Coordinated Investigations (EcoFOCI): https://www.ecofoci.noaa.gov/

Data Background and Caveats:

Zooplankton data for each region were obtained from the NOAA Fisheries Coastal & Oceanic Plankton Ecology, Production, & Observations Database, an integrated data set of quality-controlled, globally distributed plankton biomass and abundance data with common biomass units and served in a common electronic format with supporting documentation and access software. Source: https://www.st.nmfs.noaa.gov/copepod/about/about-copepod.html

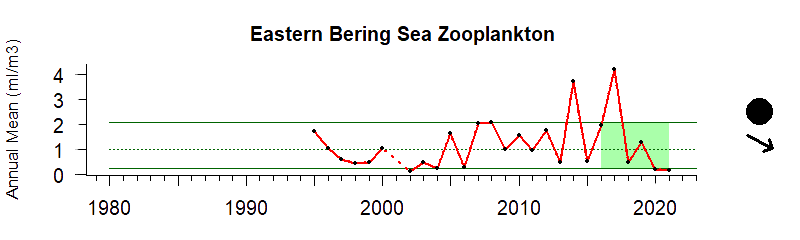

Zooplankton - Eastern Bering Sea

Between 2016 and 2021 the average concentration of zooplankton biomass showed a significant decreasing trend but was similar to historical values.

Description of time series:

Between 2016 and 2021 the average concentration of zooplankton biomass showed a significant decreasing trend but was similar to historical values.

Indicator information

Zooplankton data for each region were obtained from the NOAA Fisheries Coastal & Oceanic Plankton Ecology, Production, & Observations Database, an integrated data set of quality-controlled, globally distributed plankton biomass and abundance data with common biomass units and served in a common electronic format with supporting documentation and access software. Alaska specific data comes from the Ecosystems and Fisheries-Oceanography Coordinated Investigations (EcoFOCI): https://www.ecofoci.noaa.gov/

Data Background and Caveats:

Zooplankton data for each region were obtained from the NOAA Fisheries Coastal & Oceanic Plankton Ecology, Production, & Observations Database, an integrated data set of quality-controlled, globally distributed plankton biomass and abundance data with common biomass units and served in a common electronic format with supporting documentation and access software. Source: https://www.st.nmfs.noaa.gov/copepod/about/about-copepod.html

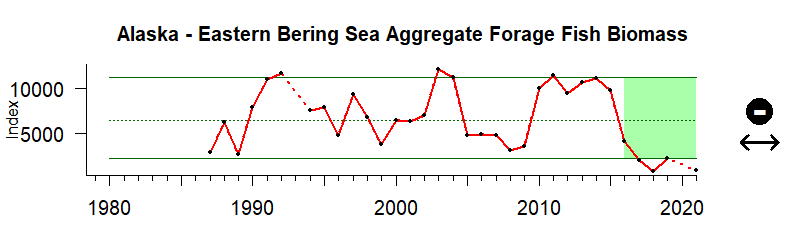

Forage Fish - Eastern Bering Sea

While there was no trend between 2016 and 2021 in the biomass of forage fish, values were below the 10th percentile historically.

Values correspond to estimated total forage biomass in millions of tons

Description of time series:

The time series describes the aggregate forage fish biomass in the Eastern Bering Sea from 1987 to 2021. While there was no trend between 2016 and 2021 in the biomass of forage fish, values were below the 10th percentile historically. Due to COVID-19 no data was collected in 2020.

Indicator source information:

This indicator from the includes adult and juvenile pollock, herring, capelin, eulachon, sandlance, pelagic rockfish, salmon, squid, and other forage fish. More information about the EBS Forage indicator can be found on the Ecosystem Status Reports For The Gulf Of Alaska, Bering Sea And Aleutian Islands page

Data background and caveats:

This index aggregates survey biomass estimates for key forage fish species in the eastern Bering Sea. The constituents are members of the “forage fish” group included as Ecosystem Components in the Bering Sea - Aleutian Islands Fishery Management Plan: eulachon, Pacific capelin, sand lance species, rainbow smelt, Pacific sandfish, and a group of minor smelt species. This aggregate does not include important forage species such as age-0 walleye pollock or Pacific herring. The biomass estimates are from the eastern Bering Sea shelf bottom trawl survey including the northwestern survey strata 82 and 90. Because this survey is not optimized for small pelagic fishes, the data should be viewed with caution.

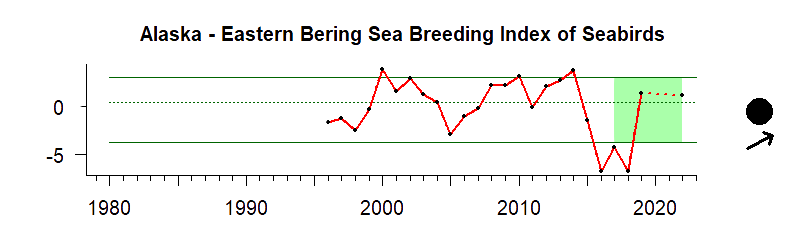

Seabirds - Eastern Bering Sea Breeding Index

The Eastern Bering Sea Breeding Index over the last 5 years saw an increasing trend and values were similar to historical values.

Values indicate estimated seabird abundance using a relative breeding index

Description of the Time Series

The Eastern Bering Sea Breeding Index over the last 5 years saw an increasing trend and values were similar to historical values.

Description of seabirds:

Seabirds are a vital part of marine ecosystems and valuable indicators of an ecosystem’s status. Seabirds are attracted to fishing vessels and frequently get hooked or entangled in fishing gear, especially longline fisheries. This is a common threat to seabirds. Depending on the geographic region, fishermen in the United States often interact with albatross, cormorants, gannet, loons, pelicans, puffins, gulls, storm-petrels, shearwaters, terns, and many other species. We track seabirds because of their importance to marine food webs, but also as an indication of efficient fishing practices.

Indicator and Source Information:

This data was compiled by the US Fish and Wildlife Service and the multivariate index is calculated by a NOAA author. The Alaska Maritime National Wildlife Refuge has monitored seabirds at colonies around Alaska in most years since the early- to mid-1970’s. Time series of annual breeding success and phenology (among other parameters) are available from over a dozen species at eight Refuge sites in the Gulf of Alaska, Aleutian Islands, and Bering and Chukchi Seas. Monitored colonies in the eastern Bering Sea include St. Paul and St. George Islands. Here, we focus on cliff-nesting, primarily fish-eating species: black-legged kittiwake (Rissa tridactyla), red-legged kittwake (R. brevirostris), common murre (Uria aalge), thick-billed murre (U. lomvia), and redfaced cormorants (Phalacrocorax urile). Reproductive success is defined as the proportion of nest sites with eggs (or just eggs for murres that do not build nests) that fledged a chick.

Data Background and Caveats:

Data only include the species listed above in the Eastern Bering Sea Sub Region of Alaska. Reproductive activity of central-place foraging seabirds can reflect ecosystem conditions at multiple spatial and temporal scales. For piscivorous species that feed at higher trophic levels, continued reduced reproductive success may indicate that the ecosystem has not yet shifted back from warm conditions and/or there is a lagged response of the prey. Despite environmental changes returning back to more neutral conditions, seabird foraging conditions do not appear to have recovered in the eastern Bering Sea. In contrast, the improvement in attendance and minimal reproductive activity among murres in the Gulf of Alaska during 2017 indicates some improvement in foraging conditions for those species. Data can be directly accessed here: https://apps-afsc.fisheries.noaa.gov/refm/reem/ecoweb/Index.php?ID=9

Close

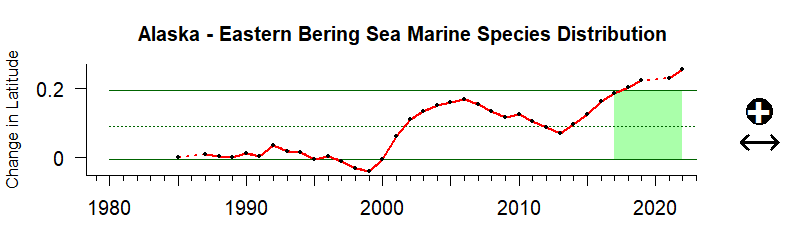

Marine Species Distribution - Eastern Bering Sea Latitude

Between 2017 and 2022 the average species latitudinal shift showed no trend but was above historical ranges, indicating a northward shift in distributions.

Values indicate annual cumulative change in centroid across all species in a region in degrees N

Time Series: Between 2017 and 2022 the average species latitudinal shift showed no trend but was above historical ranges, indicating a northward shift in distributions.

Indicator Source Information:

This data was obtained from the Distribution Mapping and Analysis Portal (DisMAP). provides important information for fisheries management including which species are caught where and at what depth.The latitudinal (or depth) centroid is the biomass-weighted center of a population’s distribution. This metric is calculated by the DisMAP portal team using the interpolated biomass distribution surface they generated from the survey catch data, such that the latitudinal (or depth) centroids are the mean latitude (or depth) of the species distribution, where each raster cell latitude (or depth) is weighted by the value of weight-per-unit-effort for that cell. Scientists at NOAA use this data to calculate each species’ centroid as the mean latitude and depth of catch in the survey, weighted by biomass. The centroid for each species is calculated for each year after standardizing the data to ensure that the measure is consistent over time despite changes in survey techniques and total area surveyed. This data provides important information for fisheries management including which species are caught where and at what depth.

Data Background and Caveats:

The regional and national marine species distributions shown here represent the average shift in the centroid of a selected core set of species that are caught every year in surveys conducted in each region. These species represent a wide range of habitats and species types. As species distributions respond to many environmental and biological factors, combining data from multiple diverse species allows for a more complete picture of the general trends in marine species distribution. In order to more easily track and display changes in these distributions, the first year is standardized to zero. Thus, the indicator represents relative change in distribution from the first survey year.

Close

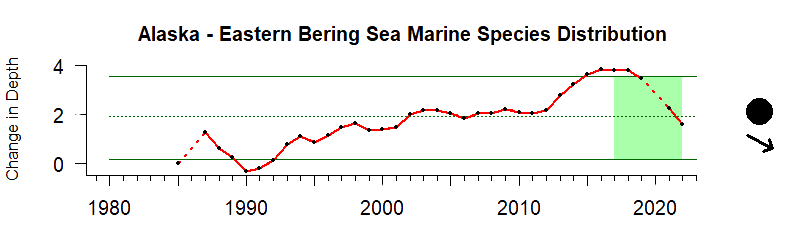

Marine Species Distribution - Eastern Bering Sea Depth

Between 2017 and 2022 the average species water column depth shift showed a significant downward trend, indicating the distribution moved deeper.

Values Indicate annual cumulative change in average species centroid depth in meters - for example, a value of -5 indicates the species centroid moving deeper by 5m.

Description of Time Series: Between 2017 and 2022 the average species water column depth shift showed a significant downward trend, indicating the distribution moved deeper.

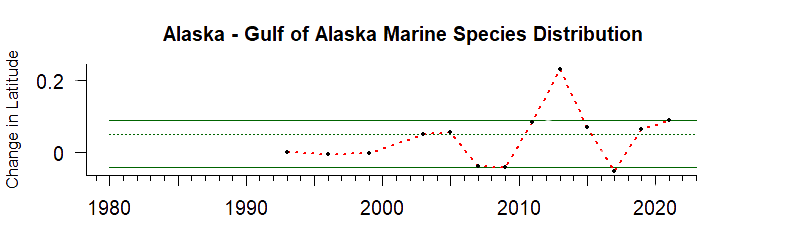

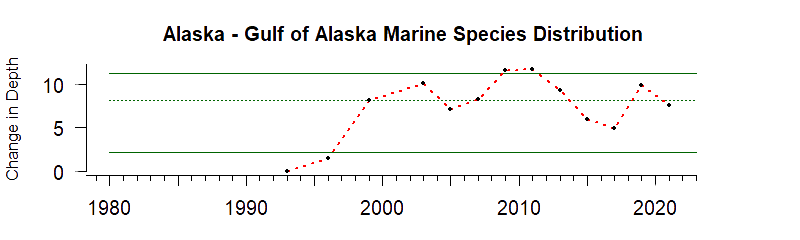

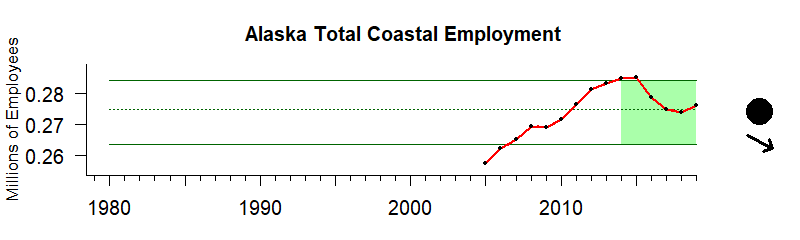

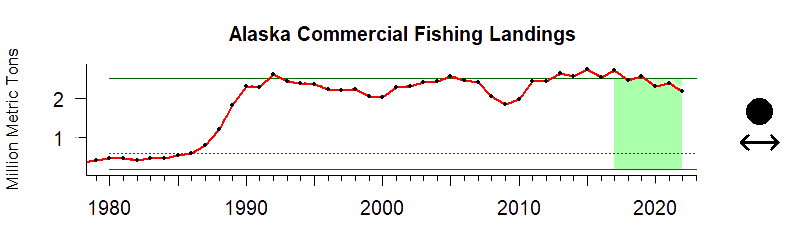

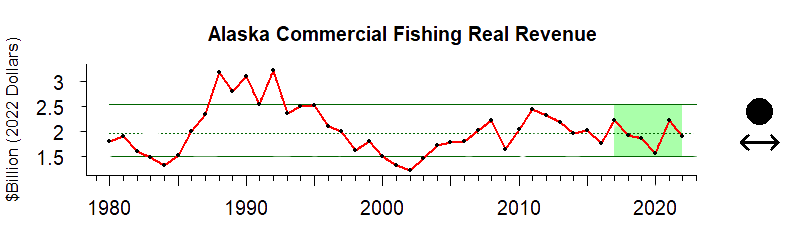

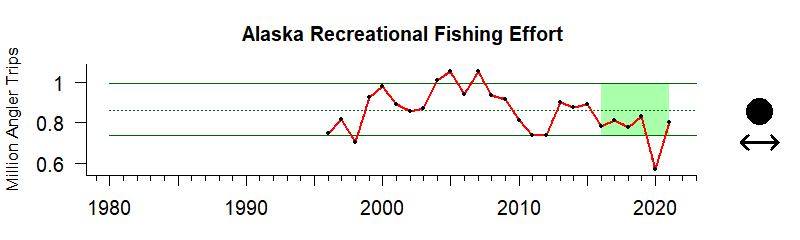

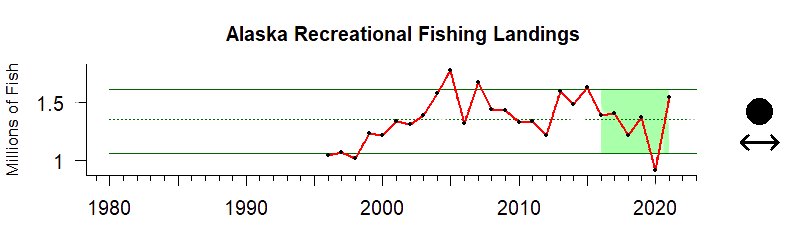

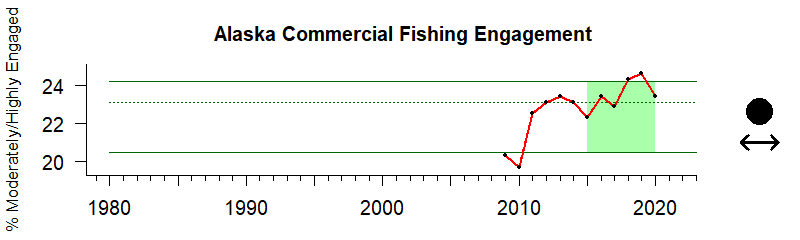

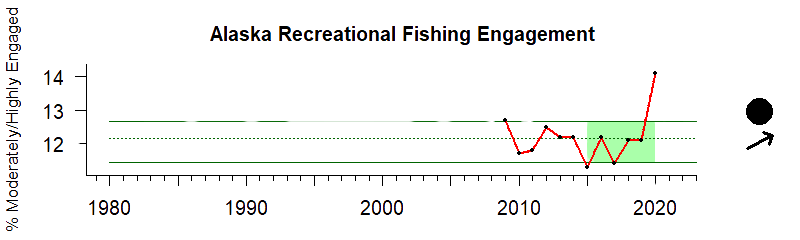

Indicator Source Information: